We left Colombo at the crack of dawn, ten of us spanning generations from 19 to 85. The city was still half asleep as we drove out. Ampara was nearly 450 kilometers away – a long drive that carried us through ever-shifting landscapes: sleepy towns, sun-baked paddy fields, and stretches of road that felt endless until the mountains finally gave way to the dry zone’s vast openness.

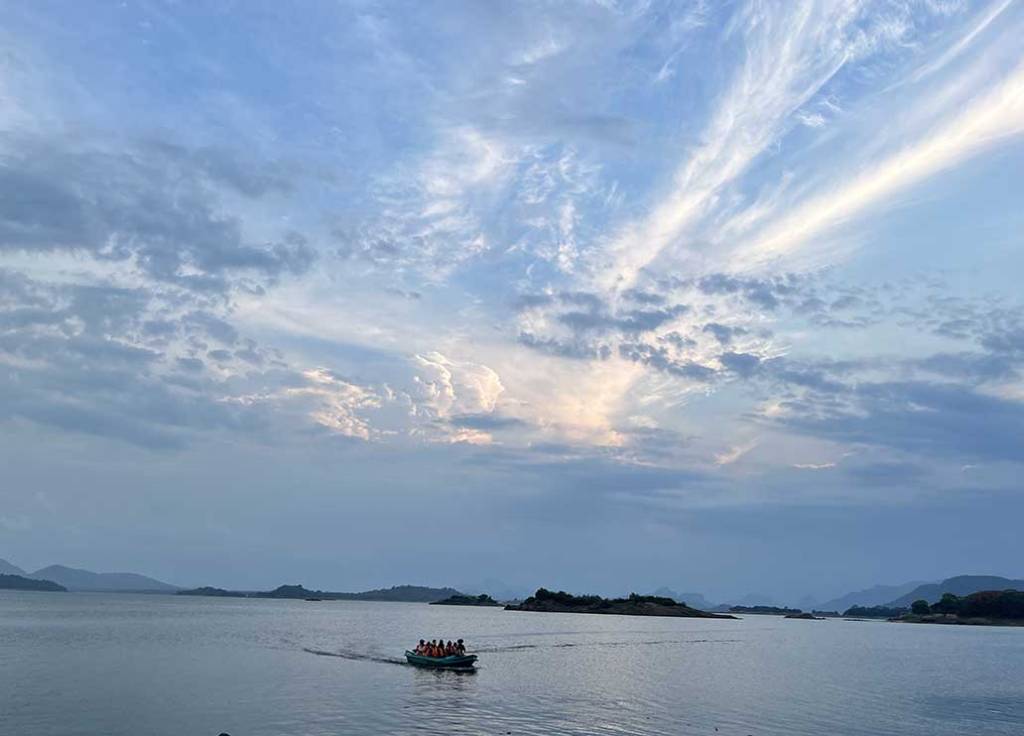

After a breakfast stop at my usual place, the Grand Pearl at Monaragala, our next stop was the vast Senanayake Samudraya. Sprawling over 30,000 acres, it is the largest reservoir in Sri Lanka, a manmade inland sea created in the 1940s under the visionary Gal Oya Development Scheme of D. S. Senanayake. Beneath its shimmering waters lie entire valleys, ancient forests, and forgotten villages, sacrificed in the name of progress. Today, the reservoir sustains farming communities and draws wildlife to its shores.

We boarded two boats that skimmed the still water beneath the still simmering afternoon. And then, on the far shore, the elephants emerged. A small herd grazed lazily at the water’s edge, calves obediently following their mothers, while lone elephants silently foraged away from the herds. Watching them from the heart of the reservoir, it felt like we were intruding on something ancient and private, a ritual that had been unfolding here long before dams and boats and cameras existed.

That night, we rested at Rajawewa Resort, simple and welcoming, where the chatter around the dinner table stretched into laughter, stories, and a comfort that only comes when family and friends gather after a long day’s journey.

The next morning, a little late and a lot lazy, we began our climb up Rajagala Rock at 10 a.m. The sun was already punishing, pressing down with a heat that clung to us like a second skin. This time, we decided to start the climb from the western side (I had already climbed this in 2022) and as the path wound steeply upward, within minutes sweat was streaming down our backs. What made it bearable was Indika, our guide, whose easy smile and endless stories wove history and folklore into every step.

Rajagala, “the Monarch’s Rock” is no ordinary mountain. Spread across more than 1,000 acres, it is one of Sri Lanka’s largest yet least-known archaeological sites, often called the “forgotten Mihintale.” Over 600 ruins lie scattered across its slopes: crumbling stupas, guardstones carved with faded patterns, meditation caves with drip-ledged entrances, and Brahmi inscriptions etched into stone, many still legible after two millennia.

History here is inseparable from spirituality. Rajagala rose to prominence in the 1st century BCE, patronized by kings who endowed it with land, tanks, and villages. But its greatest claim lies in the belief that Arahant Mahinda Thera, the son of Emperor Ashoka of India and the monk who introduced Buddhism to Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BCE, spent his final years here. Tradition holds that his relics along with those of his disciple Itthiya Thera were enshrined in a stupa at the summit.

Yet Rajagala also hums with folklore. Long before monks claimed it, legends say it was a royal fortress, its summit fortified by kings and chieftains of Digamadulla. Villagers whisper of hidden passageways and buried treasure guarded by spirits. Indika showed us a broad stone slab said to be a throne, and a hollow rock depression believed to have been a bathing pond for queens. He lowered his voice to share how locals still leave incense and flowers at certain caves not for the Buddha, but for the yakkas, protective spirits who guard the relics of Mahinda Thera to this day.

By the time we reached the summit, we were drenched, panting, our shirts plastered to our skin. But standing amid weathered stupas, looking down across the green sweep of the Digamadulla plains, with wind tugging at our clothes and legends whispering through the rocks, all discomfort dissolved. Rajagala was not just ruins on a hill; it was a living palimpsest of faith, power, and myth, layered into stone.

The descent was quicker, though no less hot. By late afternoon we were back at the base, dusty, weary, and desperate for relief. That came in the form of Navagiriya Wewa – cool, glassy waters that invited us in. We slipped gratefully into the lake, laughing, floating, feeling the heat dissolve in its embrace.

But as so often in the dry zone, calm didn’t last. The sky darkened in an instant, clouds rolling in heavy and black. Thunder cracked, lightning split the sky, and the storm broke with ferocity. We scrambled out of the lake, dripping and shivering, as sheets of rain battered the earth.

Indika, unfazed, shepherded us to his tiny home nearby. There, sheltered under his modest roof, we were greeted by his wife, who had prepared a simple lunch. Dripping water on the floor, rain drumming above, we ate rice, curries, and sambols — the kind of meal that tastes unforgettable not for its complexity, but for its warmth and timing. Outside the storm raged, but inside, it felt like the world had briefly folded into a pocket of peace.

On Sunday, our final day, before heading back, we made one last stop at Buddhangala Raja Maha Viharaya. By then the sun was merciless, radiating off the rocky surfaces as though the earth itself was aflame. Yet Buddhangala is a place that commands reverence, even in the fiercest heat.

Archaeologists trace its origins back to the 2nd century BCE, when it stood as part of the great monastic landscape of Digamadulla. Even today, its rocky slopes are strewn with the remains of stupas, monastic dwellings, and inscriptions — echoes of a vast community that once lived, studied, and meditated here. The temple’s very name, Buddhangala — “the Rock of the Buddha” — comes from the belief that relics of the Buddha himself were enshrined within one of its stupas during King Saddhatissa’s reign.

And then there is the folklore. Villagers speak of treasures hidden beneath the ruins, guarded by deities who strike down those who dare to desecrate them. Some whisper of luminous lights seen at night, drifting across the rock — said to be the radiance of the relics themselves. Others believe monks who once meditated here still linger, their spirits protecting the temple in silence.

Climbing to the top was punishing and whilst the heat shimmered in waves, every step up those sun-baked rocks a battle. Tired from the previous day, and exhausted by the simmering heat, we decided to abort the rest of this hike, leaving this journey for another day.

We left Ampara with our skins darkened by the sun, our legs aching from climbs, and our hearts full of images: elephants by the water, stupas crumbling on ancient hills, and storms breaking over lakes. Ampara had been a journey of endurance and wonder, where history whispered through stone, and folklore lingered in the wind.

Perhaps I may climb Rajagala again. As Indika says, even 7 days is not enough to explore this sacred, yet mystical place.