Day 4 of our ride began with an unexpected delight. Over breakfast, just as everyone was preparing for the long ride ahead, I brought out a bottle of Seeni Sambol—that bold, fiery essence of Sri Lanka. The surprise lit up their faces, and soon it was being heaped generously onto eggs and toast. In that familiar burst of red, far from home and wrapped in Himalayan mists, we felt a flicker of home, a bite of nostalgia—spiced and sweet—woven gently into the morning chill.

With warmth in our bellies and wide grins on our faces, we rode out of Gangtey, leaving behind its quiet monasteries and winding trails, heading east into the deeper, older heart of Bhutan.

The road climbed steadily, curling through forests of spruce and fir towards Pele La Pass. Somewhere between the bends, the landscape shifted. The trees grew sparse, the air thinner—and suddenly, we saw them: yaks. Massive, shaggy, and unbothered, they grazed lazily by the roadside, their long hair flowing in the breeze, rekindling memories of our ride through Ladakh. Our first sighting.

Descending from Pele La Pass, the landscape shifted again into lush valleys and terraced hillsides as we made our way to Trongsa.

Towering above everything was the mighty Trongsa Dzong—a fortress so vast it seemed to anchor the very cliffside. Every king of Bhutan has served as Penlop of Trongsa before ascending the throne. It is both historical and strategic, and it exudes a quiet authority.

Leaving Trongsa behind, the road climbed once again, this time towards Yotong La Pass, which marks the border between the Trongsa and Bumthang districts. The air turned crisp, and the scenery became more remote and dramatic as we ascended.

By late afternoon, we arrived at Yotong La Pass, perched at 3,400 meters. The cold here wasn’t subtle—it bit through our gloves and rushed up our sleeves. But we braved the weather and stopped for photographs that would be frozen in time—literally.

As we descended from Yotong La, the forest thickened once more—and then, like a vision from a folktale, it appeared: Chendebji Chorten.

Set in a wide, grassy clearing surrounded by pine-covered hills, Chendebji Chorten looks almost like it was plucked from Nepal and placed gently in Bhutan. And that’s no coincidence—it’s modeled after the famous Boudhanath Stupa in Kathmandu. Its white dome and tiered base gleamed against the green, serene and solitary. Built in the 18th century by Lama Shida, it was meant to subdue a demon that once haunted this valley. Today, it stands quietly, a sacred waypoint for travelers passing from west to east.

We paused here for a while, took more photos, and let the silence seep in. It felt like the mountains were listening.

From Trongsa, the road rolled and dipped until we reached Willing Waterfalls—a hidden treasure. Tucked beneath mossy cliffs, the lodge and restaurant here sit beside a crashing cascade. We lunched on a wooden deck overlooking the waterfall, and a stunningly beautiful garden, savouring fresh trout, nutty red rice, and a fiery ezay that had us reaching for chilled Coke between tearful bites. The flavours, the rush of water, the crisp mountain air—it was Bhutan served on a plate.

After that lunch, we somehow managed to hoist ourselves back in the saddle. The descent into Bumthang was cinematic—open meadows, apple orchards, and distant prayer flags waving us in.

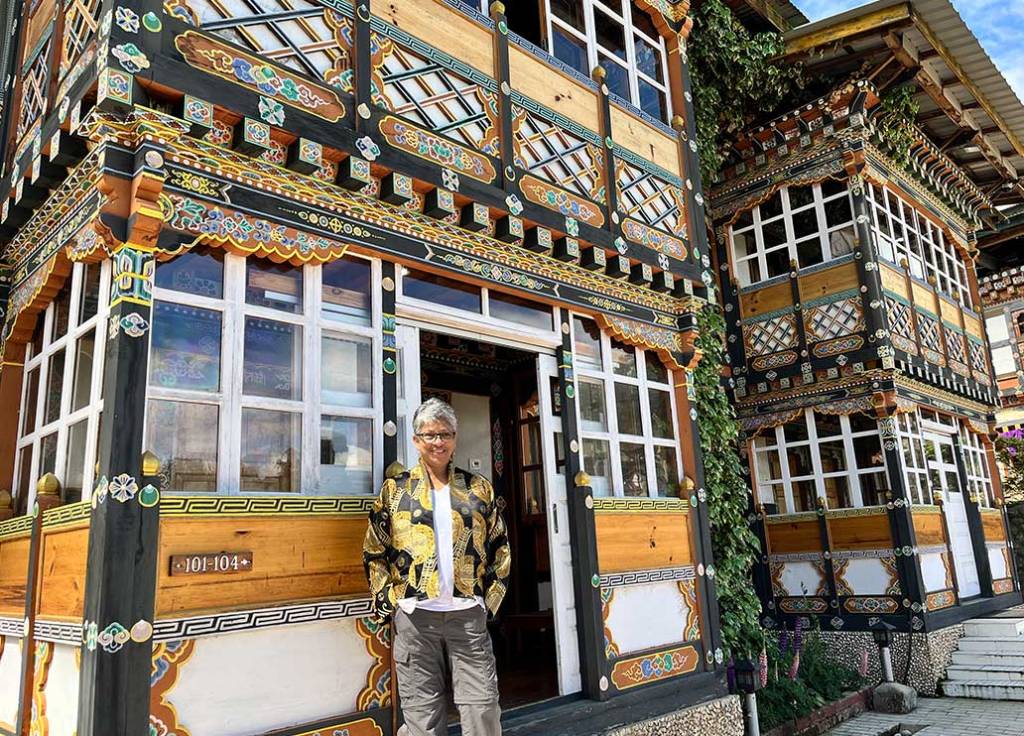

Our destination: Jakar Village Lodge, a charming, family-run retreat tucked away in a quiet grove just beyond the heart of town. It didn’t feel like checking into a hotel—it felt like being welcomed into someone’s ancestral home.

Dinner that evening was listed by Lonely Planet as one of the best meals in Bhutan, and it more than lived up to the praise. The spread was earthy, nourishing, and made entirely from scratch using ingredients from their own gardens.

We feasted on nutty buckwheat noodles, wilted ferns sautéed with garlic and butter, and a medley of fresh mountain vegetables seasoned with love and a touch of fire. Even the ezay—that fiery Bhutanese chilli paste, was perfectly balanced: bold, smoky, addictive. There were no fancy garnishes, no towering presentations—just good food, served with pride, in the soft hum of a home that had seen generations. And that, somehow, made it the most memorable meal of the journey.

We met the patriarch of the house—a former governor, now a well-traveled storyteller. Over tea, he spoke of his trip to Sri Lanka, fondly recalling Galle, Sigiriya, hoppers, and the kind-heartedness of island people.

Day 5 was a rest day—a day to sink into Bumthang’s serenity. Since the day we started this trip, this was the first morning we could sleep in.

After a hearty breakfast, we strolled into Chamkhar town, a quaint sprawl of cafés, and incense shops. Lunch was a modest affair in a family-run restaurant, where I met a lovely woman who beamed as she mentioned her daughter studying at KDU in Sri Lanka. Small world!

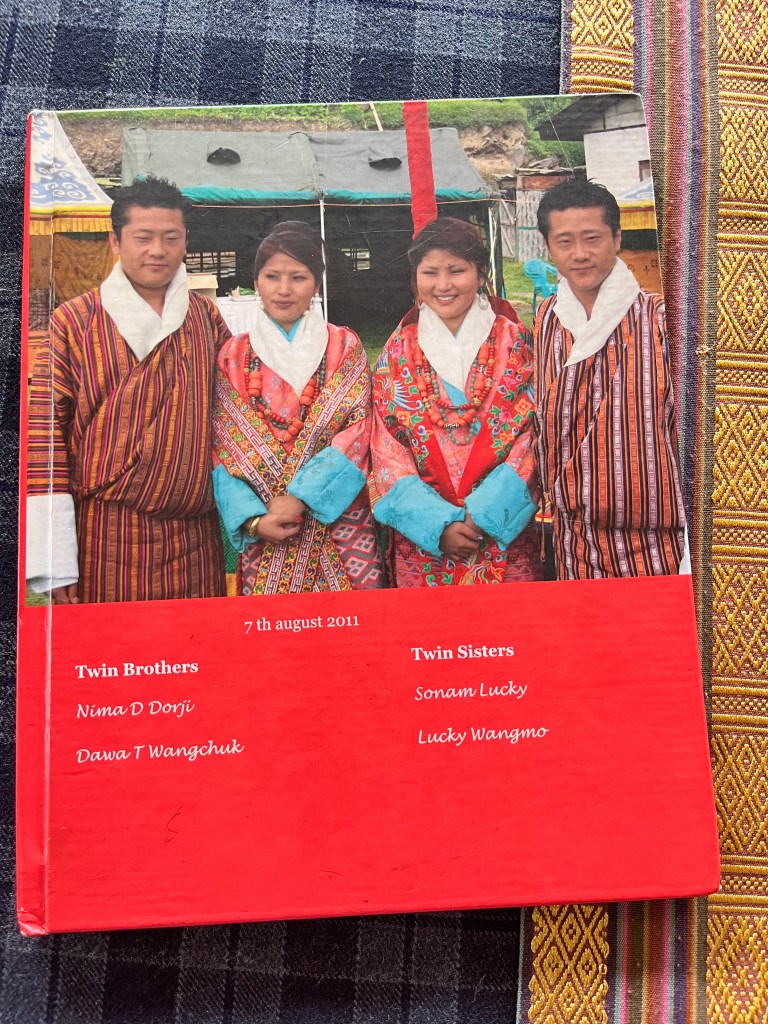

This was a moment we encountered time and again across Bhutan—a quiet dignity, an ease with the world. Whether in a remote village, a roadside lodge, or a monastery at 3,000 metres, we were constantly struck by how well-spoken, thoughtful, and globally aware the Bhutanese people are. Their deep-rooted respect for tradition walks hand in hand with a curiosity about the world. Many spoke multiple languages—Dzongkha, English, sometimes Hindi—and could converse as comfortably about climate change and Gross National Happiness as they could about yak butter and spiritual lineages.

There’s a gentleness here, but make no mistake—Bhutan’s people are not only deeply cultured; they are exceptionally educated, especially for a small Himalayan kingdom. It’s a place where monks study philosophy alongside astronomy, where students hike for hours to attend school, and where education is seen as both a right and a responsibility. The result is a society that feels deeply rooted yet remarkably open—grounded, gracious, and quietly global.

Thereafter, in the soft glow of the Bumthang afternoon, we set out to explore the valley’s sacred heart.

The vibrantly painted and timeworn Jambay Lhakhang stood with quiet grace, one of 108 temples built in the 7th century by Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo to subdue a demoness believed to be sprawled across the Himalayas. Each temple was strategically placed on a specific point of her body—this one anchoring her left knee. The legend came alive as Tshering, in his soft-spoken and reverent tone, shared these stories with us—each word adding another layer to the temple’s mystique.

Though simple in structure, the temple held layers of age and energy. Faded murals of wrathful deities and dancing dakinis covered its inner walls. The altar was dark and cool, lit only by rows of butter lamps, their golden flames mirrored in the brass bowls of water offerings.

Local lore says that once a year, during the Jambay Lhakhang Drup, naked monks perform fire rituals in the dead of night—part purification, part spectacle, part devotion. Though the festival was months away, the stories clung to the place, thick as incense.

Then, tucked just behind a row of whispering blue pines and barley fields lies Wangduechhoeling Palace—a quiet, unassuming structure that once housed royalty and now breathes history in every timber beam. We’d been encouraged to visit not just for its architecture, but to witness something more profound: a glimpse into what Bhutan’s monarchy chose to relinquish in order to live simply, humbly—like their people.

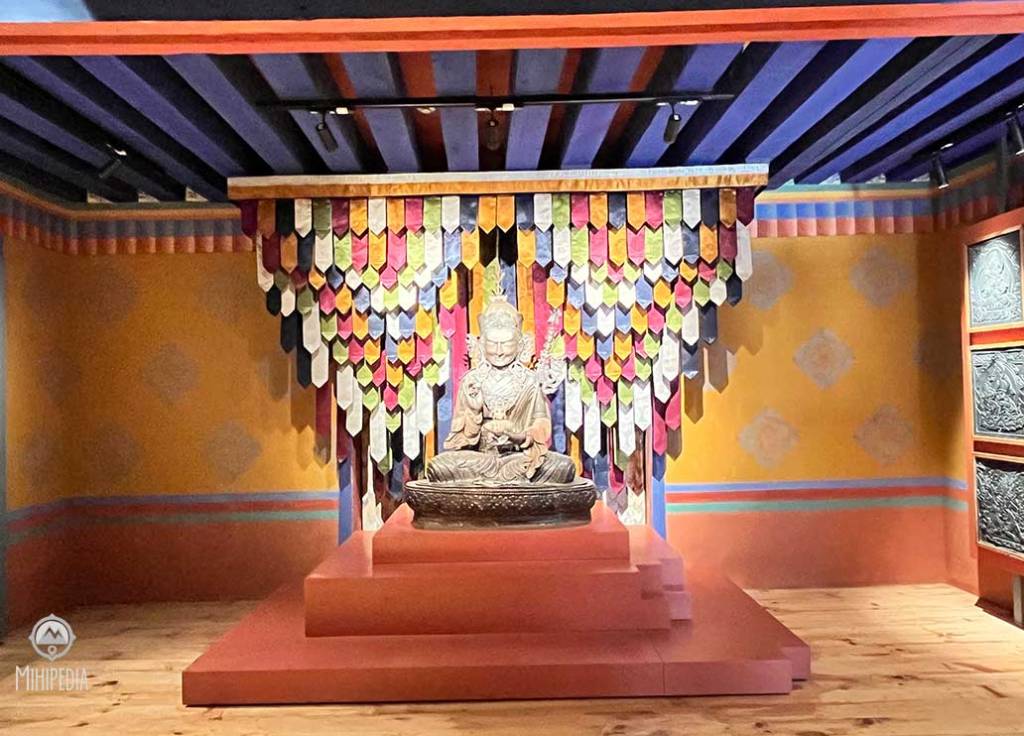

Built in the late 1850s, this was the birthplace of Bhutan’s monarchy. Unlike the grand dzongs with their imposing facades, this palace welcomes you with a sense of gentleness—more ancestral home than fortress. Recently restored and repurposed as a museum center, it now opens its soul to travelers who wish to step back into the Bhutan of kings, sages, and storied revolutions.

As we wandered through its creaking wooden corridors, we found personal artifacts, photographs, manuscripts, and ceremonial relics that offered a rare, intimate window into Bhutan’s royal past. One room still bore the marks of its former occupant—King Ugyen Wangchuck, the first monarch of Bhutan—his prayer texts resting near the window where sunlight filtered through just as it might have a century ago.

The restoration work is delicate and reverent. Nothing feels polished or overly curated. Instead, the palace retains its lived-in warmth—mud-plastered walls, faded thangkas, and the scent of incense still caught in the grain of the old wood. In a country where spirituality is often written in stone and wind, the Wangduechhoeling Museum adds another texture—one of memory, lineage, and quiet legacy. You don’t just learn history here—you feel it.

Tomorrow, we ride again. But tonight, we enjoy more homegrown hospitality and good conversation with the proprietors of Jakar Village—until I inadvertently dropped “bricks,” which earned me the moniker Gadol for the rest of the trip!

Total Distance: 161 km Total Time: 48 hours Attitude: Feeling blessed

its getting better and better. like we are still in Bhutan.

LikeLike

Yes. Can you feel the wind in your face and the smell of pine?

LikeLike

Love this 😍

Tharuka Dissanaike

LikeLike

Nothing like a good seeni sambol to ease any homesickness 🙂

LikeLike