There’s a quiet thrill in discovering history along streets I’ve driven past a hundred times. On this overcast Saturday morning, nine of us gather outside the Kotte Archaeological Museum, tucked along Kotte Road, ready to explore the remnants of a kingdom that ruled Sri Lanka long before Colombo rose to prominence – a city once known as Daaru Gama, or “Village of Trees,” a nod to the dense forests that once surrounded the early settlement.

The museum, small and shaded by trees, is well presented and wonderfully informative. Housed in a building donated by *E.W. Perera, it holds fragments of 15th-century Kotte comprising stone inscriptions, royal coins, pottery shards, and tools unearthed from the city itself. The curators, clearly proud of the collection, tell us that much of it was found beneath the very streets and homes we pass daily. Standing there, I feel humbled, realizing that beneath modern Kotte lies the memory of an empire.

From there, accompanied by Pradeep, our guide for the day who we find out to be extremely committed and knowledgeable, we set off on a loop through the ancient ruins of Kotte, weaving between narrow lanes and modern homes. Our first stop is the Alakeshwara Palace, once the residence of the formidable minister Nissanka Alakeshwara, who fortified Kotte before King Parakramabahu VI ascended the throne. What was once a sprawling complex of courtyards and chambers now survives only in fragments comprising low laterite (kabok) foundations and scattered stone pillars hidden amid modern houses. Yet, even in ruin, it speaks of power, strategy, and the early brilliance that shaped a kingdom.

Two foundations lie close to each other here, believed to be the remains of King Nissanka Alagakkonara’s palace, the powerful minister who served under King Vikramabahu III of Gampola. Architectural features and artefacts unearthed from the site, including grinding stones and water filters, support this theory. Some, however, suggest that this very spot may have also been Alakeshwara’s mausoleum, adding yet another layer of intrigue to Kotte’s buried past.

We continue to the fort ramparts, where moss-covered laterite blocks peek from shaded lanes, and to the outer moat, now overgrown, hinting at the scale and sophistication of a city designed to withstand any assault. The inner moat, once fed by the Diyawanna Oya, separated the royal precinct from the rest of the city, a clever defensive layer that ensured controlled access to the palace and key administrative areas. Though now obscured by urban development, these remnants stand as quiet reminders of Kotte’s ingenious engineering.

Even private gardens hold traces of the past. Ancient wells (oora kata) from the Kotte period, tucked away in backyards, once supplied water to the palace, monasteries, and residential quarters. Their stone and laterite walls reveal skilled craftsmanship and a glimpse into a 5th-century city that balanced function, beauty, and security.

Walking along the Diyawanna Wetland Centre, we follow what was once part of Kotte’s natural outer defence. In the 15th century, this network of marshes and waterways formed a protective moat while sustaining birds and aquatic life. It’s easy to imagine boats gliding silently through these waters, carrying soldiers, traders, and monks to and from the city. Today, the wetlands preserve biodiversity and the quiet echoes of a royal past.

Our journey takes us to Veherakanda, where grassy mounds hide the remnants of ancient stupas, and home to the Kotte Raja Maha Viharaya. This site features two ancient burial tombs, believed to belong to unknown royals or monks from the Kotte era. The stupas stand on a platform built of laterite, the smaller one entirely while the larger has a laterite base topped with brickwork. Measuring 21 feet (6.4 m) and 30 feet (9 m) in diameter, these structures date back to the Kotte Period. Traces of an image house and other monastic ruins nearby suggest that this area was once part of a large and thriving monastery, offering a quiet glimpse into the spiritual life of the ancient capital.

Back in our vehicles and inching through weekend traffic, we pass the stone Ambalama, one of Kotte’s few surviving resting posts. I’ve driven past this bustling junction countless times without a second glance, but today it takes on new meaning. Built entirely of granite, this modest structure once offered shelter to weary travellers, royal messengers, and pilgrims. Some believe it was part of Kotte’s underground tunnel system, serving as an air vent. Only this Gal Ambalama survives; the others, made of mud, disappeared by the mid-20th century.

We finally arrive at Ananda Sastralaya College, quiet and deserted on this Saturday morning. Amid the empty grounds, we find a curious ruin, a tunnel entrance, a rare trace of Kotte’s underground network. Built from stone and laterite, these tunnels are believed to have once linked the royal palace, Alakeshwara’s administrative complex, and strategic points like the Gal Ambalama. The air shafts, storage chambers, and escape routes reveal how advanced Kotte’s urban planning once was. Standing at the entrance, it isn’t hard to imagine courtiers and messengers moving silently beneath the earth while the royal city thrived above.

Pradeep leads us slightly off-route to show an indoor badminton stadium, a modern facility that now stands on what were once the outer grounds of Kotte — spaces originally used for training soldiers and royal recreation. The building itself was constructed by the British in the early 20th century, and remarkably, parts of the original structure and its old wooden benches still remain. It’s a fascinating contrast a colonial-era sports hall resting atop the training grounds of a medieval kingdom, where echoes of both history and play seem to linger in the air.

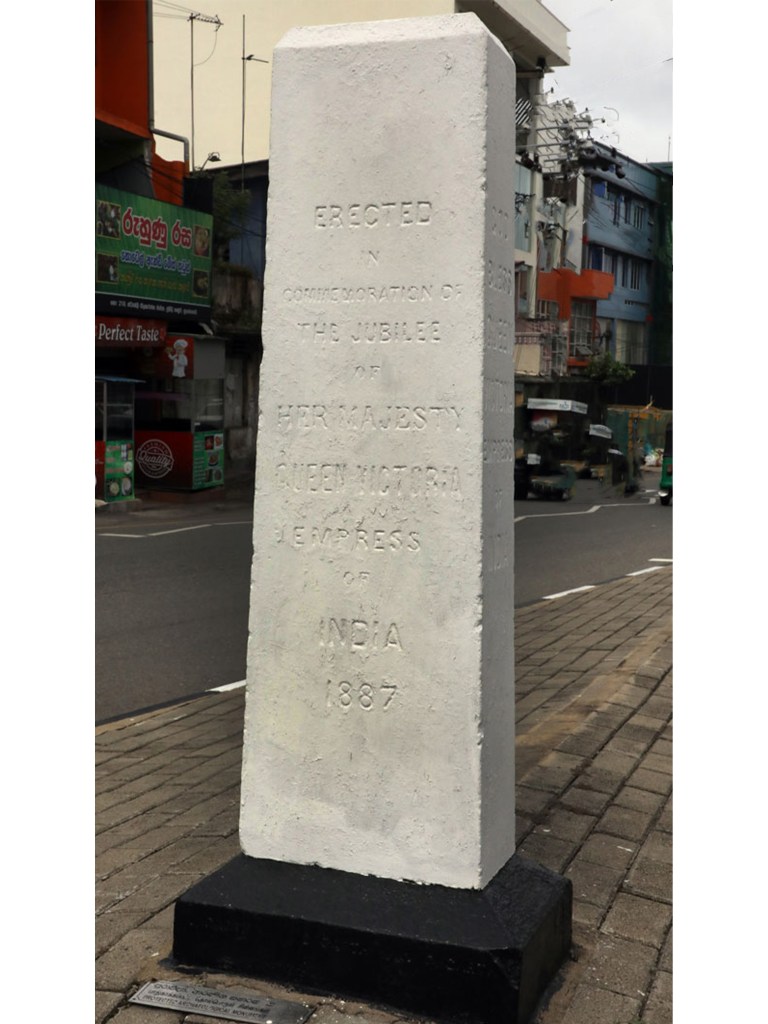

The Kotte Jubilee Post, located in Nugegoda, is a historic monument erected in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. Standing at the intersection of Stanley Thilakarathne Mawatha and Old Kottawa Road, it is maintained by the Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte Municipal Council and was officially declared an archaeological protected monument in 2005.

Our final stop is the Parakumba Raja Maha Viharaya, built on the site of Kothagantota, once the palace entrance. The well outside the rampart hints at the gate that once stood here. During King Parakramabahu VI’s reign, this site housed the royal treasury. Across the Diyawanna Oya, in Battaramulla, lived the palace cooks, a small but fascinating link between daily life and royal history.

The temple grounds hold relics from the Kotte period, traces of Dutch architecture, and a boulder crowned with a Makara Thorana, marking the highest point where Sitawaka Rajasinghe once camped during his siege.

Historically, the temple also safeguarded the Sacred Tooth Relic, kept close to the palace and venerated publicly for three months each year. Two nearby stupas, resting on laterite platforms, mark the burials of unknown royals or monks, timeless witnesses to the spiritual and political life of Kotte.

Three hours pass in what feels like minutes. From museum halls to hidden tunnels, temple courtyards to mossy ramparts, our morning in Kotte becomes a journey through layers of history, each one quietly waiting beneath the streets, gardens, and waterways of a forgotten capital.

If you haven’t explored this ancient kingdom yet, go. It’s well worth your time.

Note: E.W. Perera (1875–1953), known as “The Lion of Kotte,” was a barrister, state councillor, and freedom fighter who played a vital role in Sri Lanka’s struggle for independence. He famously carried a secret petition against British martial law hidden in his shoe to deliver it safely to the Colonial Office in London — a daring act that earned him his legendary title. His courage and conviction continue to inspire generations from his beloved Kotte.

Museum Opening Hours: Daily from 8.00 AM – 4.00 PM (including Sundays)

If you’d like more details or tips for visiting this museum or exploring this ancient Kotte Kingdom, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Thank you for sharing Babi. Enjoyed your take. So vividly described

LikeLike

Thanks Varuni. It’s amazing how much we miss on a daily basis!

LikeLike